Many of us are attracted to and fascinated by gargoyles. Their monstrous, terrifying, beautiful or ugly figures astound and intrigue us. But there’s more to gargoyles than iconography and functionality. There’s something living that changes over time, something bound up with the sculptor’s hand that speaks to us across the years and the centuries.

In today’s post, we are going to look at stone.

- Alcobaça Monastery (Portugal)

- El Burgo de Osma Cathedral (Spain)

The Language of Stone

Although some gargoyles are made of other materials, such as ceramic, wood or metal, the most frequently employed material is stone, due to its water and weather resistance.

Generally, whenever it was of acceptable quality, local stone was used to construct most of the buildings in a city, as is the case of Zamora with its local sandstone, and Salamanca with its Villamayor stone. Williamson observes that when the faithful approached the cathedrals, they could see that the sculpture was inseparable from the architecture, and the same remains the case today, and the stone that was used for architectural sculpture was generally the same as that used for the rest of the building. This also applies to the gargoyles, since in most cases these were sculpted from the stone used to construct the building they adorned.

The most frequently employed types of stone are sandstone, limestone and granite. When I was studying the gargoyles in the cathedrals of Castile and León, I discovered some interesting properties of the stone used to sculpt the gargoyles, thanks to works by the authors listed in the references given at the end. Here are a few of these characteristics.

Used to construct the Cathedral of Salamanca, the sandstone from Villamayor is mostly fine-grained and pale ochre in colour, with darker red streaks and veining. It is a very soft stone that is easy to work, becoming harder over time as it loses moisture.

Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

In Ávila, the cathedral and other monuments were mainly built using three kinds of granite. The first of these is grey granite, known as gris Ávila, which is mainly composed of quartz, feldspar, mica and chlorite. It presents very low values for porosity, water absorption and vapour permeability combined with high mechanical strength, all characteristics of high quality granite. The second is ochre granite (known as Caleño), which presents high porosity and permeability values and poor mechanical strength. In addition to quartz, traces of feldspar and dioctaedric mica, it contains laminar silicates and iron oxyhydroxides. It has important ornamental properties (colour, easy to work) and was often used in the past to construct monumental buildings in Ávila (e.g. the cathedral and San Vicente). The third kind of granite is known as piedra sangrante (bleeding stone), which presents values for porosity and mechanical strength that are mid-way between the previous two, and is highly decorative because iron oxides are redistributed during stone formation, creating a red and white marbling effect. The stone also contains abundant opal. Several varieties have been used in the cathedral, depending on the time of construction and restoration, and also on the strength and aesthetic features required. Grey granite has generally been used for replacements, probably because of its better resistance to deterioration.

- Ávila Cathedral (Spain)

- Ávila Cathedral (Spain)

- Ávila Cathedral (Spain)

Nevertheless, the stone most frequently used to sculpt gargoyles is limestone, a carbonated rock of sedimentary origin, composed of carbonate precipitates and carbonated or other particles. This is a high quality stone for construction and sculpting, and is easy to cut due to its low abrasiveness, permitting many creative possibilities.

As we can see, the type of stone used was fundamental when sculpting gargoyles. Since these sculptures were sited on the exterior of buildings, exposed to the elements, the stone underwent inevitable transformations, including colour changes, fractures, cracks and erosion. As we said earlier, these changes converted the gargoyles into “living” matter as they sustained change and metamorphosis.

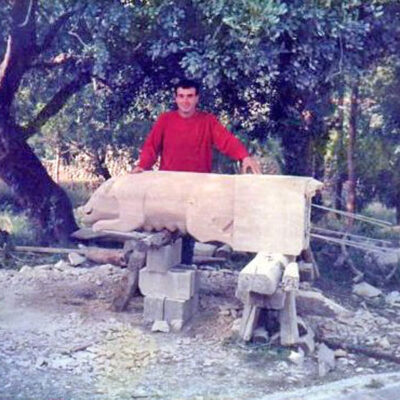

Let’s look now at what happens to a block of stone in the hands of a sculptor. It is time to give shape to the gargoyle that will eventually emerge from the artist’s handiwork, and depending on the period, the shape of the figure destined to adorn the gargoyle and its iconography will vary.

As we saw in a previous post, although gothic gargoyles first appeared —according to Viollet-le-Duc— around 1220 in the French cathedral of Laon, we know that gargoyles have existed since antiquity. Initially, they were usually small and consisted of heads, especially of a lion, as can be seen in some classical Greek examples.

- The Parthenon of Athens (Greece)

- National Archaeological Museum of Athens (Greece)

- National Archaeological Museum of Athens (Greece)

The shape and type of sculpting employed in the Middle Ages to create gargoyles convey important chronological information. Various authors (e.g. Morales Baena, Rebold Benton and Viollet-le-Duc) have discussed their history. In general, the oldest gargoyles (Romanesque and early Gothic) are short, robust and roughly worked. They are also schematic, in most cases heads or busts, and usually represent animals. This iconography is similar to that of the classical gargoyles described above.

- Ciudad Rodrigo Cathedral (Spain)

- Ciudad Rodrigo Cathedral (Spain)

- Ciudad Rodrigo Cathedral (Spain)

Subsequently, the figures became more slender and elongated, supported by corbels that allowed them to jut out and direct the water as far away from the walls as possible. Real animals, humans, hybrids, fantastical animals and grotesque devils were all depicted. In the late 13th century, the figures started to become more exaggerated and caricature-like, while the sculpting now became finer and more detailed. Viollet-le-Duc also says that these longer, more slender gargoyles, in which animals were often replaced by human figures, became widespread in the 14th century and by the 15th century had become even more refined and acquired a more ferocious aspect. Powerful figures were sculpted by skilled hands with great attention to detail. We would add that they also acquired more expressiveness and dynamism.

Although they are all magnificent and a reflection of different periods, I must confess my predilection for the elongated, stylised gargoyles representing surprising creatures and sculpted with great attention to detail. Contemplating them from the road, and above all from the rooftops, is an indescribable experience. Some are so slender and so long that they appear to be about to launch into flight.

- Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

- León Cathedral (Spain)

- Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

- Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

The early years of the Renaissance produced gargoyles that still preserved the Gothic style of the 15th century ones, but towards the second half of the 16th century, sculptors rejected Gothic forms and, with few exceptions, their gargoyles became simple geometric tubes or pipes, a characteristic that continued in the Baroque.

Ávila Cathedral (Spain)

As we always say, field work shows us that stone speaks, conveying through shape, texture, erosion, style and the very figure itself an entire period, with its artistic fashions, skills and ways of thinking and living. Contemplating the gargoyles at close range, every one of their parts, every gesture, every fracture, every shape and changing colour of the stone is an authentic and marvellous lesson for those of us who adore gargoyles.

Bibliography consulted

GARCÍA DE LOS RÍOS COBO, J. I. y BÁEZ MEZQUITA, J. M., La piedra en Castilla y León, Valladolid, Junta de Castilla y León. Consejería de Economía y Hacienda. Dirección General de Industria, Energía y Minas, 1994.

MORALES BAENA, A. M., Las gárgolas del claustro del monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes de Toledo, Tesis inédita dirigida por M. Prieto Prieto, Departamento de Pintura-Restauración. Facultad de Bellas Artes. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 1994 (leída en 1995).

REBOLD BENTON, J., Holy Terrors. Gargoyles on medieval buildings, New York, Abbeville Press, 1997.

VICENTE, M. A., MOLINA, E. y RIVES, V., “Piedras ornamentales en las catedrales de Ávila y Salamanca: Naturaleza y comportamiento” en A. Sancho Campo (director), Las Catedrales de España. Jornadas técnicas de conservadores de las catedrales. Alcalá de Henares, 6 y 7 de noviembre de 1998, Máster de Restauración y Rehabilitación del Patrimonio. Cuadernos Temáticos del Patrimonio nº 2, Alcalá de Henares, Conferencia Episcopal Española. Instituto Español de Arquitectura. Universidad de Alcalá. Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Madrid. Junta de Castilla y León, 1998.

WILLIAMSON, P., Escultura Gótica. 1140-1300, Madrid, Ediciones Cátedra, S. A., 1997.

VIOLLET-LE-DUC, M., Dictionnaire Raisonné de l´Architecture Française du XIe au XVIe Siècle par M. Viollet-le-Duc, Architecte du Gouvernement, Inspecteur-Général des Édifices Diocésains, Tome Sixième, Paris, F. de Nobele Libraire, 1967.

Doctor of Art History and researcher specializing in the study of gargoyles.

I am Dolores Herrero Ferrio, and my thesis, “An Approach to the Study of Gargoyles of Gothic Cathedrals in Castilla and León”, is dedicated to the study of these fascinating figures.

If you like gargoyles and art history, you will also enjoy my book, “The Gargoyle and Its Iconography,” a book I have written with great care for those interested in the world of gargoyles.

I have created my own Encyclopedia of Gargoyles, a Gargopedia to share with you, where you will discover all the secrets and wonders of these enigmatic sculptures.

I hope you enjoy this Gargopedia as much as I have enjoyed creating it, and remember that each gargoyle has a story to tell, and here you will discover them all.