Gargoyles are not only fascinating sculptural elements—they also serve a crucial purpose within architectural structures. In this introductory article, we explain what a gargoyle is, its function as a water spout, and the role these sculptures played in medieval architecture. This is an essential starting point to understand their artistic value as works of art, their technical function as drainage elements, and their significance as historical heritage.

From Water Spout to Work of Art

This blog is dedicated to gargoyles—those magnificent, majestic sculptures perched on medieval buildings, silently observing us from above across the centuries. They are, at once, marvels of engineering and remarkable artistic creations.

Who doesn’t love gargoyles? Very few people are indifferent to them. Most are drawn to their presence. Every time we pass a building adorned with gargoyles, we instinctively look upward. These fantastic and captivating figures never fail to intrigue passersby in streets and squares.

While originally functional, many gargoyles have become ornamental over time—either due to weathering and disuse or because new drainage systems have been installed.

Frequently Asked Questions About Gargoyles

• What are gargoyles?

• What is the origin of gargoyles?

• What is their function or meaning?

• What kinds of figures do gargoyles depict?

• Where can gargoyles be found?

• Who created gargoyles?

• Are gargoyles demons? Why do some depict demonic figures?

• What do the gargoyles of Notre Dame symbolize?

These are some of the most common questions people ask—questions we will explore throughout this blog.

Our Journey Begins: What Is a Gargoyle?

When undertaking a study or research on gargoyles, it’s essential to define this term. Although it may seem obvious, the word gargoyles is frequently used to refer to all kinds of creatures decorating the walls of buildings, and because they depict the same sorts of figures as gargoyles, they’re all included in the same description.

The Oxford dictionary defines the gargoyle as “a grotesque carved human or animal face or figure projecting from the gutter of a building, typically acting as a spout to carry water clear of a wall”. This definition clearly explains what gargoyles are, so any figure of a monster, animal, demon, etc. decorating a wall is not a gargoyle if it doesn’t have a spout to drain water through. These depictions placed on buildings aren’t gargoyles for drainage, they’re decorative images, sometimes known as chimera or grotesques, like the ones by Viollet-le-Duc on Notre Dame in Paris.

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral (Spain)

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral (Spain)

- León Cathedral (Spain)

- Girona Cathedral (Spain)

- León Cathedral (Spain)

The Etymology of the Word “Gargoyle”

In terms of its etymology, it appears in Latin as gargŭla (throat or gullet) and also as gargărīzo from the Greek γαργαρίζω (to gargle). In French, gargoyle is gargouille and the verb gargouiller means to make a sound like that of liquid in a pipe, to gurgle.

The Functional Role of Gargoyles in Medieval Architecture

The appearance of gargoyles marked a huge step forward in finding a solution to the difficult problem of water drainage, enabling water to flow out of their mouths in narrow jets and preventing it from running down walls and damaging stonework.

Simón García described the gargoyle as being there “so water does no harm” (S. García, Compendio de architectura y simetría de los templos (1681), Universidad de Salamanca, 1941).

The Expansion of Gargoyles During the Middle Ages

According to Viollet-le-Duc, gargoyles appeared on medieval buildings around 1220 at Laon Cathedral (in France), and by around 1240 they were being used systematically in Paris. During the 13th century they became the preferred method for draining water. However, we know that gargoyles had been in use since Antiquity.

In the Gothic period, the use of gargoyles for drainage meant that large buildings like cathedrals could be planned following a complex and perfect drainage system that you can see today by going up on the rooftops, where you can follow the channels that take water to the gargoyles. On cathedrals you can also see the magnificent flying buttresses channelling the water to be drained away through the gargoyles’ mouths.

Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

León Cathedral (Spain)

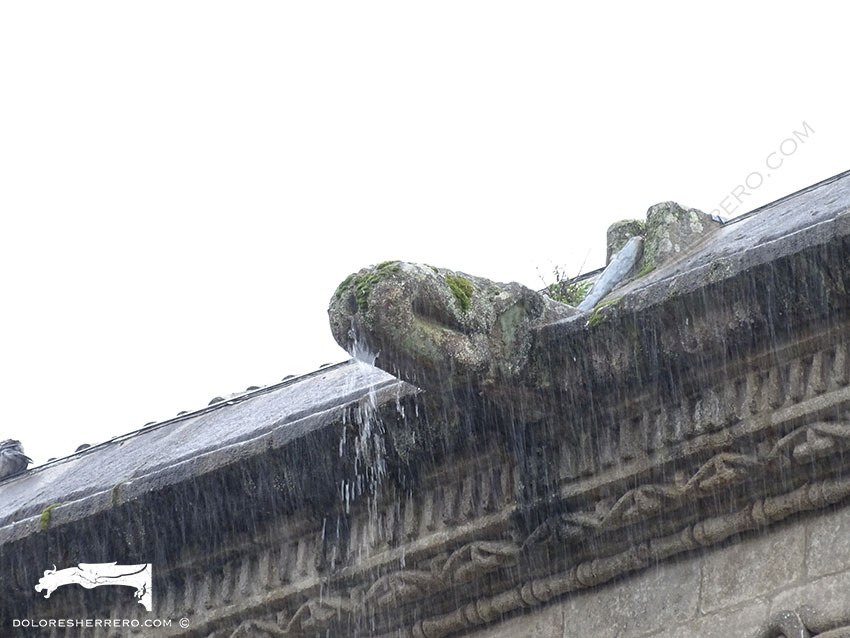

On rare and fortunate occasions, we have been able to photograph gargoyles in action—actually spouting water. For instance, during a rainy visit to the Monastery of Batalha in Portugal, at the cathedral in Guarda, and at the National Palace of Mafra during one of our projects. We also had this opportunity during a storm in Girona, which allowed us to capture the beautiful gargoyles of its cathedral, and, of course, on one of our research trips to Santiago de Compostela.

Historically, gargoyles have often been seen simply as functional elements—decorated spouts integrated into architectural design with a very specific and practical purpose.

Fortunately, in recent years, gargoyles have increasingly been studied not only as functional features but also as unique sculptural works of great artistic merit. Witnessing them in action is both fascinating and moving. Here, we share some images of gargoyles fulfilling their original purpose.

Photographic Examples: Gargoyles in Action

Gargoyles of Girona

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

- Cathedral

Basilica of Sant Feliu

Gargoyles of Portugal

- Batalha Monastery

- Batalha Monastery

Guarda Cathedral

- National Palace of Mafra

- National Palace of Mafra

- National Palace of Mafra

Gargoyles of Santiago de Compostela

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Old Hospital of San Roque

- Royal Hospital

- Royal Hospital

- Cathedral

Bibliography

REBOLD BENTON, J., Holy Terrors. Gargoyles on medieval buildings, New York, Abbeville Press, 1997.

SOBRINO GONZÁLEZ, M., “El cimborrio y otras soluciones a las cubiertas en la arquitectura altomedieval”, Actas del Cuarto Congreso Nacional de Historia de la construcción. Cádiz, 27-29 de enero de 2005 (edición a cargo de S. Huerta), vol. II (2005), pp. 1017-1027.

VIOLLET-LE-DUC, M. (s. XIX), Dictionnaire Raisonné de l´Architecture Française du XIe au XVIe Siècle par M. Viollet-le-Duc, Architecte du Gouvernement, Inspecteur-Général des Édifices Diocésains, Tome Sixième, Paris, F. de Nobele Libraire, 1967.

Doctor of Art History and researcher specializing in the study of gargoyles.

I am Dolores Herrero Ferrio, and my thesis, “An Approach to the Study of Gargoyles of Gothic Cathedrals in Castilla and León”, is dedicated to the study of these fascinating figures.

If you like gargoyles and art history, you will also enjoy my book, “The Gargoyle and Its Iconography,” a book I have written with great care for those interested in the world of gargoyles.

I have created my own Encyclopedia of Gargoyles, a Gargopedia to share with you, where you will discover all the secrets and wonders of these enigmatic sculptures.

I hope you enjoy this Gargopedia as much as I have enjoyed creating it, and remember that each gargoyle has a story to tell, and here you will discover them all.