In today’s post we continue examining one of the most amazing and intriguing gargoyle topics, the gesturality of the body and its expressive force.

In the first part we looked at two habitual gestures in gargoyles: pulling on the mouth ― and other parts of the body ― and placing the hand on the throat. In this chapter we’ll be discovering other bodily gestures, a clear expression of plasticity in art.

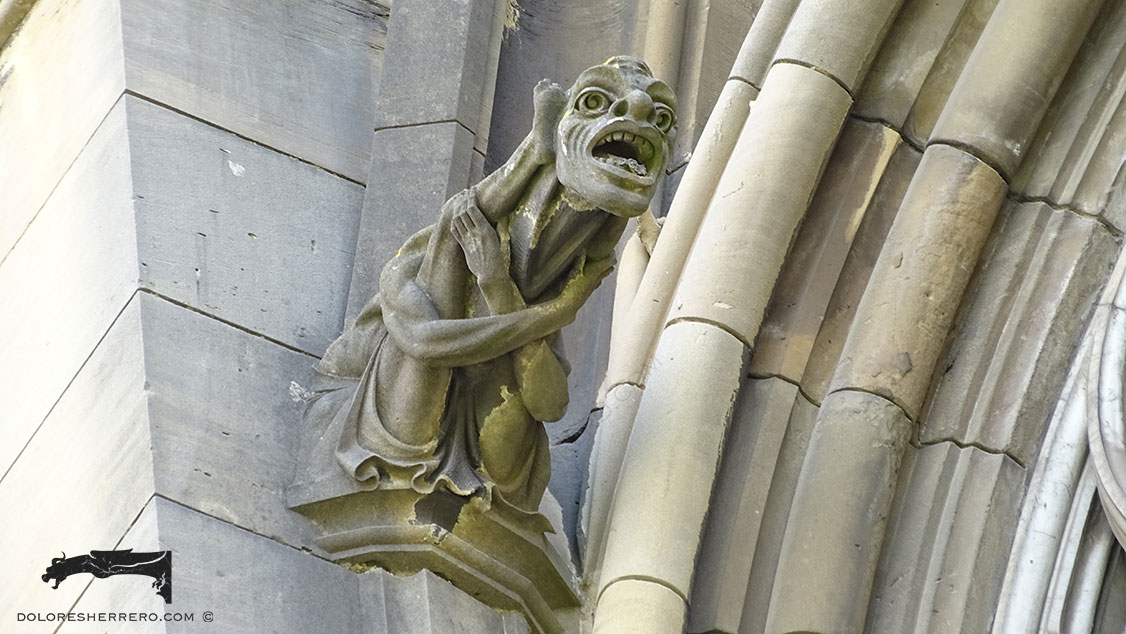

There’s a diverse range of hand movements in gargoyles. In fact, you can see hands placed on any part of the body, not only on the mouth or the throat, but on the head, the chest, the face, the ears, the genitals, the knees, the lap, etc., as well as showing different actions: holding some sort of object or small creature, meditating, praying, working and so on.

Generally speaking, these gestures are accompanied by great expressiveness, revealing emotions and feelings (suffering, anger, desperation, pain, pleasure, devotion, withdrawal), although they can also be entertaining, comical or grotesque gestures with no intention of displaying emotions, portrayed just for fun.

- Batalha Monastery (Portugal)

- Church of St. Gangolf in Trier (Germany)

- Church of Our Lady in Trier (Germany)

- Batalha Monastery (Portugal)

- Church of Our Lady in Trier (Germany)

- Mirepoix Cathedral (France)

- Perpignan Cathedral (France)

- Palencia Cathedral (Spain)

- Batalha Monastery (Portugal)

- Brussels City Hall (Belgium)

- Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

- Batalha Monastery (Portugal)

Also connected with these kinds of playful, mocking figures is the gesture of sticking out one’s tongue. Research into its meaning leads us to believe that it’s a kind of mockery that could be a sign of disrespect and contempt for the sacred, a common gesture used in the portrayal of evil creatures and people of low class. This is seen especially in devilish figures which, from the late Gothic onwards, become images that are more comical than terrifying. Some authors think that the stuck out, protruding tongue comes from the classic Gorgon, although it also appears in depictions of the Egyptian Bes, probably known by Coptic monks, according to Link. The exact meaning of this gesture can only be imagined. The intention may simply be to depict a crude, threatening gesture that is often accompanied by foliage-covered heads (green man). However, the meaning might also be more witty. It was generally thought that exhibiting the genitalia was to keep the forces of evil at bay. Sheridan and Ross argue that the sticking out tongue may have been thought to have similar powers, so it may be that these heads looking down from high up on sacred buildings may have been intended to keep demonic forces under control. Similarly, art historian Michael Camille says that this is an offensive gesture seen in many Medieval faces, based on the apotropaic power of the classic Gorgon, where the tongue is a clear substitute for the penis and its power to prevent the evil eye. This small protuberance sliding out of the creature’s moist mouth defines it as something masculine; the tongue was a dangerous, obscene organ. Rebold Benton also connects the gesture of sticking out the tongue with Satan, who sticks his tongue out to make fun of his victims. A prominent tongue also symbolises traitors, heretics and blasphemers.

- Bordeaux Cathedral (France)

- Brussels City Hall (Belgium)

Likewise, gargoyles are shown with various leg gestures and movements, a dynamic and vividly eloquent gesture that generally gives the figures great plasticity. You can see various signs and movements that also indicate actions (dancing, attacking, fighting, etc.), seated and rampant figures, crouching and kneeling figures, figures with heads or bodies turned to one side, with crossed legs or arms, and so on. According to Camille, crossed legs symbolise arrogance.

- Tours Cathedral (France)

- Bern Cathedral (Switzerland)

Some figures, human in particular, are shown with contortionist gestures. Le Goff tells us that contortionists, along with prostitutes, were the archetypes of a gestural practice linked to demonic possession and they were outlawed during the 13th century. In his Etimologies (7th century) St. Isidore says that circus games were created for pagan celebrations. “Therefore, those who attend them as spectators are considered to serve devil worship by their very presence”.

Grotesque. Cathedral of María Inmaculada in Vitoria (Spain)

Once again, history and art join forces to show us the exciting connection between the images and their symbolism, their power of attraction and the fabulous learning and enjoyment gained, both from the images for their artistic beauty and from the meaning that always reveals a symbolism related to the historic, social, moral and psychological factors that formed part of the collective imagination in the Middle Ages.

Bibliography consulted

CAMILLE, M., El ídolo gótico. Ideología y creación de imágenes en el arte medieval, Madrid, Ediciones Akal, S. A., 2000.

CAMILLE, M., The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame. Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, 2009.

GÓMEZ GÓMEZ, A., El Protagonismo de los otros. La imagen de los marginados en el Arte Románico, Bilbao, C. E. H. A. M./E. A. H. I., 1997.

GRIVOT, D., Le diable dans la cathedrale, Paris, Editions Morel, 1960.

KENAAN-KEDAR, N., Marginal Sculpture in Medieval France. Towards the deciphering of an enigmatic pictorial language, Hants (England) and Vermont (USA), Scolar Press and Ashgate Publishing Company, 1995.

LE GOFF, J. y TRUONG, N., Una historia del cuerpo en la Edad Media, Barcelona, Ediciones Paidós Ibérica, S. A., 2005.

LINK, L., El Diablo. Una máscara sin rostro, Madrid, Editorial Síntesis, S. A., 2002.

REBOLD BENTON, J., Holy Terrors. Gargoyles on medieval buildings, New York, Abbeville Press, 1997.

SAN ISIDORO DE SEVILLA, Etimologías, II (Libros XI-XX), texto latino, versión española, notas e índices por J. Oroz Reta y M. A. Marcos Casquero, Madrid, Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, de La Editorial Católica, S. A., 1982.

SHERIDAN, R. y ROSS, A., Grotesques and Gargoyles. Paganism in the Medieval Church, London, David & Charles: Newton Abbot, 1975.

Doctor of Art History and researcher specializing in the study of gargoyles.

I am Dolores Herrero Ferrio, and my thesis, “An Approach to the Study of Gargoyles of Gothic Cathedrals in Castilla and León”, is dedicated to the study of these fascinating figures.

If you like gargoyles and art history, you will also enjoy my book, “The Gargoyle and Its Iconography,” a book I have written with great care for those interested in the world of gargoyles.

I have created my own Encyclopedia of Gargoyles, a Gargopedia to share with you, where you will discover all the secrets and wonders of these enigmatic sculptures.

I hope you enjoy this Gargopedia as much as I have enjoyed creating it, and remember that each gargoyle has a story to tell, and here you will discover them all.