Gargoyles and Dogs: Symbolism of an Ancestral Bond

We’re combining art and history once again to link magnificent gargoyle sculptures with the history of the symbolism of the figures they most commonly depict.

We’ve already looked at the symbolism of the lion, which, together with eagles and dogs, are the animals you see most often on gargoyles.

Today we’ll be looking into the symbolism of the dog.

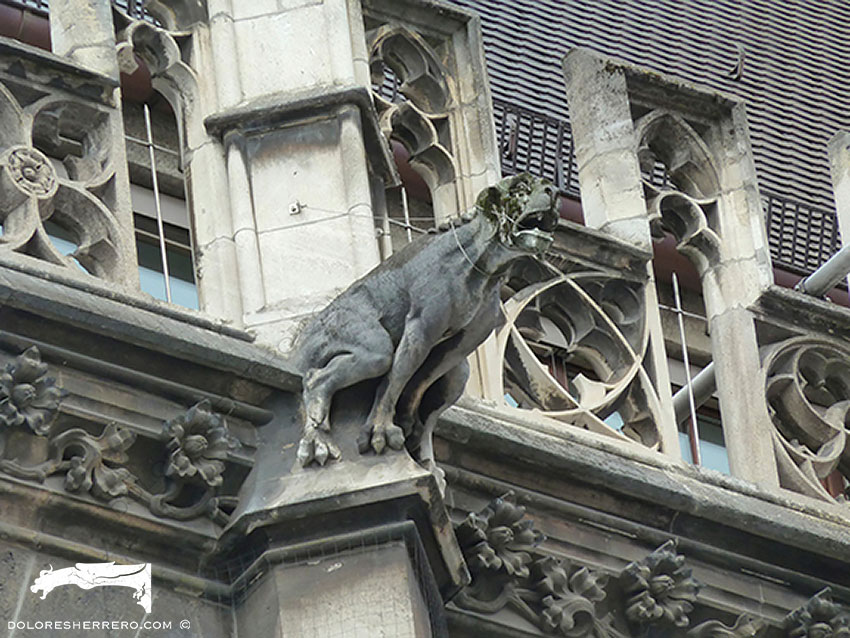

Narbonne Cathedral (France)

The Symbolism of the Dog in Gargoyle Iconography

Like we saw when we analysed the figure of the lion, the dog also appears in bestiaries and literature as well as in other works where you can discover both its symbolism and its positive and negative powers. As you already know, the way animals are portrayed usually refers to these powers and in many cases they serve to symbolise human virtues and faults.

Loyalty, Protection, and Faithfulness: The Dog as a Positive Symbol

An example of loyalty and vigilance, the dog is seen as the protector of the home and the people who live there. There’s the shepherd dog, which guards its flock and protects it against wolves, just like the priest watches over and protects his faithful flock from the devil.

They can be a symbol of loyalty, like Tobias’s dog or Saint Roch’s dog, which took bread to the saint and licked his wounds. The dog is also a symbol of loyalty in marriage, appearing in many portraits at the feet or on the lap of a married woman.

In portrayals of Saint Dominic of Guzmán, a dog carrying a lighted torch in its mouth is often shown with the saint. According to the legend, when his mother was pregnant with him, she dreamt that a little dog leapt from her womb carrying a flaming torch in its mouth. The woman made a pilgrimage to the abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos to ask for an explanation of her dream. The meaning she was given was that her son would light the flame of Christ in the world through pilgrimage, and in gratitude she named her son Dominic (Domingo in Spanish). White and black dogs – the colours of the Dominican monks’ habit – have sometimes been used as a symbol of this Order: Domini canes (dogs of the Lord).

The Dog in Medieval Bestiaries: Symbolism in the Work of Bianciotto

Continuing with this section on art and history, Bianciotto describes his work Bestiaires du Moyen Âge. Pierre de Beauvais, Guillaume le Clerc, Richard de Fournival, Brunetto Latini, Jean Corbechon, on the subject of Medieval bestiaries. In it he talks about the dog and its symbolism:

There are various species of dogs: some are used to hunt big game; others birds; others guard homes, and this is because they love their masters.

There was once a time when a powerful man was captured by his enemies and his dogs went with him, this is the kind of love a dog is capable of.

The dog heals its wounds by licking them with its tongue. The dog that heals its wound with its tongue are the priests who “lick” our wounds, or rather our sins, with their tongue, or rather with their rebukes at confession.

It is the kind of animal that eats what it vomits. The dog that eats its own vomit is a symbol for those who repeat the sins they have confessed to earlier.

If a dog crosses a water course with bread or meat in its mouth and sees its image in the water, it imagines there is a another piece there, opens its mouth to pick it up and loses the piece it already had. The dog that drops what it already had in the water because it covets the shadow it sees, represents ignorant people and men stripped of reason who covet things they do not know and abandon what they already have, so they do not obtain what they covet and completely lose what they abandoned.

The fact that a dog with a wounded belly heals itself of the internal harm, means that the word of God judges the secret thoughts of men’s hearts. If the dog eats little, it means that man must avoid overeating or drinking to excess. There is no easier way for the devil to harass the Christian than through the gluttony of the mouth.

The Negative Symbolism of the Dog in Medieval Literature

There is also literature on the negative symbolism of dogs. Eusebius of Caesarea (3rd to 4th century) in his Ecclesiastical History, compares the dog to the devil, basing his view on the Cerberus. Although the Middle Ages recovered the symbolic meaning of the dog as man’s loyal friend, some Medieval texts portray it as the symbol of some vices and sins, such as envy, and in the Libro de los Enxiemplos (14th century) it is shown as the personification of hypocrites, flatterers and ingrates. Similarly, various sources set out the idea that, in order to be able to make contact more easily with man, the devil sometimes takes on the form of a dog, his loyal and inseparable companion.

Gargoyles in Images: The Dog as a Symbolic and Emotional Figure

We now present a selection of gargoyle images depicting this magnificent animal. You will see an extraordinary variety of forms and styles, born of the imagination and creativity of gargoyle sculptors across different periods.

May this entry serve as a tribute to the “man’s best friend” — the most loyal companion, ever devoted and protective of his master.

International Gallery of Dog-Shaped Gargoyles

Gargoyles of Belgium

- Brussels City Hall

- Brussels Cathedral

- Brussels Cathedral

- Brussels Cathedral

Brussels Cathedral

Gargoyles of France

- Monolithic Church in Saint-Émilion

- Mirepoix Cathedral

- Church of Saint-Martin in Limoux

- Narbonne Cathedral

- Perpignan Cathedral

- Bordeaux Cathedral

- Basilica of St. Nazaire in Carcassonne

- Basilica of St. Nazaire in Carcassonne

Narbonne Cathedral

Augustinians Museum in Toulouse

Gargoyles of Germany

- Aachen Cathedral

- Aachen Cathedral

- Trier Cathedral

- New City Hall in Munich

Gargoyles of Portugal

- Batalha Monastery

- Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon

Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon

Gargoyles of Spain

- San Isidoro in León

- Parish of San Pedro in Gata (Cáceres)

- Monastery of San Martín Pinario in Santiago de Compostela

- Church of Santa María la Mayor in Valderrobres (Teruel)

- Church of Robledo de Chavela (Madrid)

- Collegiate Church of San Martín de Tours in Bonilla de la Sierra (Ávila)

- Plasencia Cathedral

- Lleida Old Cathedral

- Valencia Cathedral

- Valencia Cathedral

- Sigüenza Cathedral

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral

- Astorga Cathedral

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral

- Palencia Cathedral

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral

- Burgos Cathedral

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral

- Palma de Mallorca Cathedral

- Astorga Cathedral

- Gargoyle from the Casa de las Conchas (Salamanca). It is a real animal: a dog.

- Town Hall in La Fresneda (Teruel)

- House of Shells in Salamanca

- Bergós House in Torre del Compte (Teruel)

- Casa da Parra in Santiago de Compostela

- Basilica of Sant Feliu in Girona

La Fresneda (Teruel)

The Collegiate church of San Antolín in Medina del Campo (Valladolid)

Gargoyles of Other Countries

Shanghai Cathedral (China)

Milan Cathedral (Italy). Photograph by Lola Custodio

This entry was originally published in June 2017 and updated in August 2023.

Bibliography

Bestiaires du Moyen Âge. Pierre de Beauvais, Guillaume le Clerc, Richard de Fournival, Brunetto Latini, Jean Corbechon (mis en français moderne et présentés par G. Bianciotto, Série “Moyen Âge”, dirigée par D. Régnier-Bohler), París, Editions Stock, 1992.

FERGUSON, G., Signs & symbols in Christian Art, New York, Oxford University Press, 1961.

MATEO GÓMEZ, I., Temas profanos en la escultura gótica española. Las sillerías de coro, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Instituto Diego Velázquez, 1979.

REBOLD BENTON, J., Holy Terrors. Gargoyles on medieval buildings, New York, Abbeville Press, 1997.

Doctor of Art History and researcher specializing in the study of gargoyles.

I am Dolores Herrero Ferrio, and my thesis, “An Approach to the Study of Gargoyles of Gothic Cathedrals in Castilla and León”, is dedicated to the study of these fascinating figures.

If you like gargoyles and art history, you will also enjoy my book, “The Gargoyle and Its Iconography,” a book I have written with great care for those interested in the world of gargoyles.

I have created my own Encyclopedia of Gargoyles, a Gargopedia to share with you, where you will discover all the secrets and wonders of these enigmatic sculptures.

I hope you enjoy this Gargopedia as much as I have enjoyed creating it, and remember that each gargoyle has a story to tell, and here you will discover them all.

Gargoyles of the Loge de Mer in Perpignan (France): Sculptural Expressiveness in a Gem of Civil Gothic Architecture

Gargoyles of the Loge de Mer in Perpignan (France): Sculptural Expressiveness in a Gem of Civil Gothic Architecture Gargoyles Shaped Like Lions: Symbolism and Representation

Gargoyles Shaped Like Lions: Symbolism and Representation Gargoyles of Martín Muñoz de las Posadas (Segovia, Spain) as a Testament to Castilian Rural Art

Gargoyles of Martín Muñoz de las Posadas (Segovia, Spain) as a Testament to Castilian Rural Art Gargoyles and Unusual Animals: Part Two

Gargoyles and Unusual Animals: Part Two Gargoyles on the Seu Vella of Lleida (Spain): Guardians of the Fortified Cathedral

Gargoyles on the Seu Vella of Lleida (Spain): Guardians of the Fortified Cathedral