In today’s post we’ll be discussing two-headedness in gargoyles. To delve into the fascinating world of these monstrous creatures, we’ll start with a general explanation of the meaning of creatures with two or more heads or limbs.

On the topic of the multiplication of limbs or features in art, Gombrich says that this kind of accumulation makes the figures depicted more frightening (the Hydra with seven heads, the Cerberus, etc.). This theory is connected with the idea of the need to protect places and buildings that has existed since Antiquity, such as the guardian bulls of Assyria (2150-612 BC) flanking the entrances to cities and palaces, with five legs so their bodies could be seen as being complete from any direction. Generally speaking, the idea was that these figures should take on terrible, demonic forms to appear more dangerous and threatening, the apotropaic figures that we discussed when we talked about symbolism in gargoyles.

Prophetic books are a fundamental source of monsters for art history, and this time we find an abundance of examples of beings with a multiplication of heads or limbs. In Daniel’s vision of the four beasts, they are described as a lion with eagle’s wings, a bear, a leopard with four wings and four heads, and the fourth with ten horns and another small horn he saw sticking out and that had eyes and a mouth (Daniel 7, 1-9). However, the most complete source can be found in Revelations: the red dragon with seven heads and seven diadems and ten horns (Satan), the dragon that St. Michael and his angels would fight with (Rev. 12, 3-10 and 20, 1-7). Or the beast rising out of the sea with ten diadems and seven heads with blasphemous names, similar to a leopard but with bear’s feet and a lion’s mouth. And another beast, at the service of the previous one, with two lamb’s horns and speaking like a serpent (Rev. 13, 1-13). We also have the vision of the four living beings full of eyes, the Tetramorph (Rev. 4, 6-9).

In his Inferno, Dante talks about several mythological beings, such as the Cerberus (Canto VI, 21-24). His work is above all an essential source for demonic iconography: “…lay a dragon with outstretched wings, and it scorches every one he meets” (Canto XXV, 21-24); or “… a six-footed serpent darted in front of one of them…” (Canto XXV, 48-51). And the magnificent description of Lucifer: “I marvelled when I saw that, on his head, he had three faces: one, in front, blood red;/ and then another two that, just above the midpoint of each shoulder, joined the first; and at the crown, all three were reattached; […] / Beneath each face of his, two wings spread out, as broad as suited so immense a bird: I’ve never seen a ship with sails so wide./ They had no feathers, but were fashioned like a bat’s; and he was agitating them, […] He wept out of six eyes; and down three chins, tears gushed together with a bloody froth./ Within each mouth—he used it like a grinder—with gnashing teeth he tore to bits a sinner, so that he brought much pain to three at once” (Canto XXXIV, 36-57). This connection of the multiplication of features and limbs with the devil is associated with the figure of the gastrocephalus, which we talked about in a previous post.

Research carried out by Baltrušaitis says that sources which have always fed into fantasy, legends and monsters come from classic Antiquity, from Islam and from the Far East, like Sumerian multi-headed deities or the Hittite demon Tell-Halaf with two lion’s mouths from Phoenicia, India and Egypt. This leads us to think that in the West, throughout history, we have been reinterpreting and readapting them. We can see this idea in some monsters, for example, such as the figures with several arms on Eastern deities and the contribution of Saint Isidore when he refers to men with numerous hands and of Marco Polo when he talks about the idols on the island of Zipangri with several faces and hands.

The image of the two-headed creature can be linked to the god Janus (or “Janus two-faced”), the god who observes East and West at the same time. Some identify him with the sun and he is depicted with two faces as the lord of both gates of heaven because he opens and closes the day. He is portrayed with a key in one hand and a stick in the other to show that he presides over and is guardian of gates and passages. He has two faces because he rules over the sea, the heavens and the earth. Everything opens and closes to his will and he alone makes the world turn on its poles.

Also in the two-headed category is the two-headed eagle, a monstrous, fantasy creature that we often see depicted in gargoyles. Monreal Casamayor says there are antecedents of two-headed eagles in the peoples of Asia Minor, such as the Hittites, 2000 years before Christ. The Hittites saw this bird as a symbol of sovereignty and the two-headed eagle was a figure used in decorative art. The same author says that it was probably introduced in Europe with the crusades, which took the idea from the Muslims, who were already familiar with it, and later used on Christian coats-of-arms with its distinguished, stylised design. In heraldry the two-headed eagle is used as an emblem of some empires, an imperial eagle, symbol of royalty.

We invite you to see gargoyles with two-headed figures. In Spain, we have fascinating examples that are worth seeing.

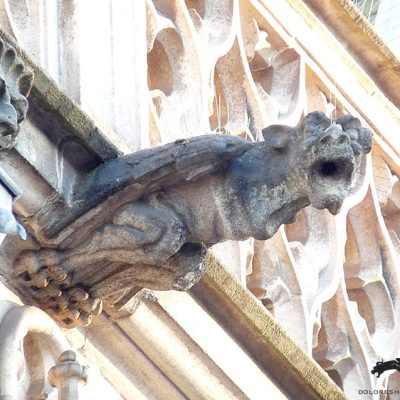

Images of two-headed creatures in gargoyles

- Segovia Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Plasencia Cathedral (Spain)

- Palencia Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Palencia Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Palencia Cathedral (Spain)

- Ciudad Rodrigo Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Burgos Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Segovia Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

- Ávila Cathedral (Spain)

- Salamanca Cathedral (Spain)

Bibliography consulted

ALIGHIERI, D., Comedia. Infierno, traducción, prólogo y notas de A. Crespo, Barcelona, Editorial Seix Barral, S. A. Biblioteca Formentor, 2008.

BALTRUŠAITIS, J., La Edad Media fantástica. Antigüedades y exotismos en el arte gótico, Madrid, Ediciones Cátedra, S. A., 1987.

GOMBRICH, E. H., El sentido del orden. Estudio sobre la psicología de las artes decorativas, Madrid, Editorial Debate, S. A., 1999.

MONREAL CASAMAYOR, M., “De sermone heráldico II: el águila”, Emblemata, nº 12, 2006, pp. 289-329.

NOËL, J. F. M., Diccionario de Mitología Universal, Vol. II, Barcelona, Edicomunicación, S. A., 1991.

Doctor of Art History and researcher specializing in the study of gargoyles.

I am Dolores Herrero Ferrio, and my thesis, “An Approach to the Study of Gargoyles of Gothic Cathedrals in Castilla and León”, is dedicated to the study of these fascinating figures.

If you like gargoyles and art history, you will also enjoy my book, “The Gargoyle and Its Iconography,” a book I have written with great care for those interested in the world of gargoyles.

I have created my own Encyclopedia of Gargoyles, a Gargopedia to share with you, where you will discover all the secrets and wonders of these enigmatic sculptures.

I hope you enjoy this Gargopedia as much as I have enjoyed creating it, and remember that each gargoyle has a story to tell, and here you will discover them all.

Gargoyles on the Eastern Side of the New Cathedral of Salamanca (Spain): An Unusual and Exquisite Ensemble

Gargoyles on the Eastern Side of the New Cathedral of Salamanca (Spain): An Unusual and Exquisite Ensemble Gargoyles of Indonesia: Mythical Faces in Traditional Asian Architecture

Gargoyles of Indonesia: Mythical Faces in Traditional Asian Architecture Gargoyles on the University of El Burgo de Osma (Soria, Spain): Tradition and Art in Stone

Gargoyles on the University of El Burgo de Osma (Soria, Spain): Tradition and Art in Stone Gargoyles of the Burghers’ Lodge in Bruges (Belgium)

Gargoyles of the Burghers’ Lodge in Bruges (Belgium) Gargoyles Shaped Like Animal Monsters

Gargoyles Shaped Like Animal Monsters